Memo: Your Letter to the Washington Post

Item

- Other Media

-

c021_003_007_011_tr.txt

c021_003_007_011_tr.txt - Transcription (Scripto)

- Read Full Text Only

- Extent (Dublin Core)

- 5 Pages

- File Name (Dublin Core)

- c021_003_007_011

- Title (Dublin Core)

- Memo: Your Letter to the Washington Post

- Description (Dublin Core)

- Memorandum regarding Dole's letter to the editor of the Washington Post being published, the Senate Finance Subcommittee hearing on Social Security's disability programs, and Senator Chafee's vote on children's SSI. Includes an Washing Post article on children's SSI.

- Date (Dublin Core)

- 1995-06-18

- Date Created (Dublin Core)

- 1995-06-18

- Congress (Dublin Core)

- 104th (1995-1997)

- Topics (Dublin Core)

- See all items with this valueChildren with disabilities

- See all items with this valueFamily policy

- See all items with this valueDisabilities

- See all items with this valueSupplemental security income program

- Policy Area (Curation)

- Social Welfare

- Creator (Dublin Core)

- Vachon, Alexander

- Record Type (Dublin Core)

- memorandum

- Names (Dublin Core)

- See all items with this valueUnited States. Social Security Administration. Office of Supplemental Security Income

- See all items with this valueChafee, John H., 1922-1999

- Rights (Dublin Core)

- http://rightsstatements.org/vocab/CNE/1.0/

- Language (Dublin Core)

- eng

- Collection Finding Aid (Dublin Core)

- https://dolearchivecollections.ku.edu/?p=collections/findingaid&id=54&q=

- Physical Location (Dublin Core)

- Collection 021, Box 3, Folder 7

- Institution (Dublin Core)

- Robert J. Dole Institute of Politics, University of Kansas, Lawrence, KS

- Archival Collection (Dublin Core)

- Alec Vachon Papers, 1969-2006

- Full Text (Extract Text)

-

(page 1)

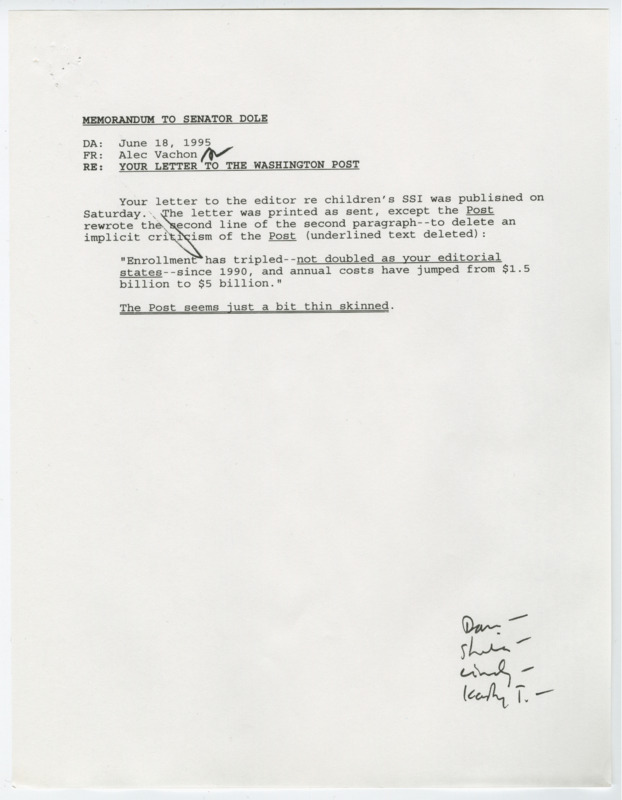

MEMORANDUM TO SENATOR DOLE

DA: June 18, 1995

FR: Alec Vachon

RE: YOUR LETTER TO THE WASHINGTON POST

Your letter to the editor re children's SSI was published on Saturday. The letter was printed as sent, except the Post rewrote the second line of the second paragraph--to delete an implicit criticism of the Post (underlined text deleted):

"Enrollment has tripled--not doubled as your editorial states--since 1990, and annual costs have jumped from $1.5 billion to $5 billion."

(doubly underlined) The Post seems iust a bit thin skinned.

(handwritten) Dan; Sheila; (unreadable two names)

(page 2)

WASHINGTON POST, JUNE 16, 1995, (SATURDAY), PAGE A16.

Preserving the Purpose of Children's SSI

A June 7 editorial ("Replacing a Kill With a Cure") called on me to forge a compromise on children's Supplemental Security Income (SSI). As The Post notes, I voted against an amendment on this matter offered by Sen. Kent Conrad during the Finance Subcommittee's markup on welfare reform. That's because I thought Chairman Bob Packwood did a better job in his bill.

Some facts. Enrollment has trippled since 1990, and annual costs have jumped from $1.5 billion to $5 billion. Three factors are responsible. First, Congress instructed the Social Security Administration to find children who belonged in the program. That's fine.

Second, in 1984, in a bill I helped craft, Congress directed Social Security to improve evaluations of children with mental disabilities. It took six years, with considerable prompting from members of Congress, including myself. That caused big growth, but again it was on Congress's orders.

But Social Security went further in 1991, adding new rules that admitted children with modest conditions into a program for children with severe disabilities. Congress did not authorize these rules, and the Finance Committee voted to repeal them.

I did not support Sen. Conrad's amendment because, in my view, it's the wrong policy and could kill the entire program. There are two reasons for this. It would put into statue the lax eligibility regulations, and it would officially convert this program from one for disabled children to a general welfare program.

In 1972, Congress created SSI to provide a cash income to poor elderly and disabled adults unable to work. Needy children were included to help their families with extra expenses resulting from the children's disabilities. But the best data we have indicate that up to two-thirds of families do hot have any extra expenses, and that the money is spent for general household purposes. That is why we have Aid to Families with Dependent Children- although the SSI check is a lot bigger.

There is also the issue of fairness. There is a small number of families-about 5 percent-with huge expenses. No extra expenses or huge expenses, all children get the same check.

The Finance Committee has not tackled these problems yet, but it should and I believe it will.

The Finance Committee bill tightens eligibility, but not as much more than the Conrad proposal. And the Finance Committee bill treats children affected by the new rules more generously. All children would have their situations reviewed again to see if they requalify, and, in any case, no child would leave the program before Jan. 1, 1997. The Conrad proposal could drop some children almost immediately.

As the editorial notes, I have been a long-standing advocate for people with disabilities. I am proud of my record. But not every program for the disabled is perfect, and this is one such case.

BOB DOLE

U.S. Senator (R-Kan.)

Washington

(page 3)

MEMORANDUM TO SENATOR DOLE

DA: March 16, 1995

FR: Alec Vachon

RE: SENATE FINANCE SUBCOMMITTEE HEARING ON "SOARING COSTS OF SOCIAL SECURITY'S TWO DISABILITY PROGRAMS"

* The Subcommittee on Social Security & Family Policy will meet on Wednesday, March 22, 1995, at 10:00 a.m. in Dirksen 215, to examine the sharp growth in the SSI and SSDI over the past 5 years. For example, between 1989 and 1994, SSI rolls jumped 42%, from 4.1 to 5.8 million recipients, and expenditures from $15 to $24 billion. CBO projects SSI rolls will increase by 2.2 million persons by 2000, and expenditures will rise to $42.5 billion. BTW, this will be the first Finance hearing on any aspect of SSI since 1986.

* [N.B. Subcommittee hearing is preparation for full Committee hearing during week of March 27th on SSI reform proposals--which will focus on cuts in eligibility for children, aliens, and drug addicts/alcoholics.]

* WITNESSES ON MARCH 22ND:

--Senator William S. Cohen;

--Social Security Commissioner Shirley S. Chater;

--David Koitz of the Congressional Research Service; and

--The Honorable Jim Slattery, Chairman, Childhood Disability Commission.

Yvonne indicates your schedule is open at that time

DO YOU WISH TO ATTEND THE SUBCOMMITTEE HEARING?

YES (blank) NO (handwritten check mark)

IF YES, DO YOU WANT ME TO PREPARE AN OPENING STATEMENT FOR YOU?

YES (handwritten check mark) NO (blank)

cc: S. Burke

(handwritten) Dan; Sheila

(page 4)

(handwritten) Alev V- (unreadable)

THE WASHINGTON POST, JUNE 18, 1995 (SUNDAY), P. C7.

Teaching Johnny to Fail

The Mixed-Up Messages ofDisability Welfare for Troubled Kids

By Heather Mac Donald

ANOTHER CHILDREN's welfare debate is about to hit Congress-reform of the federal benefits program for disabled poor children, known as Supplemental Security Income.

Congress could not have chosen a more emotionally charged issue. Welfare advocates are already preparing images of children dumped in the streets if the proposed House and Senate bills become law.

Yet the people who work most closely with poor children-teachers, pediatricians and social workers-argue that SSI puts marginally disabled or non-disabled children on the dole life and often hides the children's real problem: abusive or neglectful parents. These front-line observers should be heard.

Children's SSI has expanded enormously in the last five years, driven by three powerful economic incentives: Parents receive roughly three times more money from SSI than from Aid to Families with Dependant Children; states save money by shifting their AFDC caseload to SSI since the latter is funded by the federal government, with optional state supplementation; and mothers with disabled children are exempt from welfare work requirements.

Until 1990, however, the Social Security Administration kept the demand for SSI in check by restricting benefits to children with a medically defined severe impairment, such as cerebral palsy or cystic fibrosis. But in 1990, the Supreme Court ordered the agency to include children whose disabilities were not severe if they were unable to function in an "age-appropriate" manner.

The result was dramatic. The number of children receiving SSI shot up threefold: 900,000 children will collect $5 billion this year. Another 200,000 children will join the rolls by the end of 1995.

The Supreme Court also radically altered the composition of the rolls, by opening them to the vast and growing world of learning and behavioral disorders. Children who fall behind in school or who act violently in class may now be classified as functionally disabled.

Two-thirds of the new beneficiaries since 1990 claim "mental impairment."

Although many teachers and social workers support disability payments for the severely disabled, it is hard to find proponents for the program as now structured.

"Teachers are disgusted with it," says Jeff Nussbaum, a special education music teacher at Park West High School in Manhattan. "A kid gets classified as 'emotionally disturbed.' What that means is anyone's guess. He can be violent, really rotten, and he gets the dole."

In effect, critics argue, SSI has created a perverse incentive system for parents: "Parents whose children ahve minimal handicaps try to get their children into special education classes so their kids can qualify for SSI," complains a school psychologist at New York's Central Park East Secondary School. A student at a New York City elementary school recently told a story in a symbolic play class that illustrates the impact of SSI on the nation's poorest communities. Acting out her tale with dolls, she describes a mother of four who had adopted two more children. Although the new siblings weren't working out, the mother planned to keep them anyway, the girl explained, because she wanted the extra $100 in SSI payments they were bringing in.

"This was a special education student," says Beth Mahaney, a school psychology aide. "She doesn't understand much, but she already understands how the system works."

Some teachers believe that the prospect of SSI payments leads parents to coach their children to fail classes or misbehave in school. Eighty-one percent of instructors and special education counselors polled in Arkansas said they believe their students on SSI had been told by their parents to act up in class, and 79 percent taught that once a child qualifies for SSI, his motivation to succeed decreases. The Social Security Administration, however, has been unable to document such parental coaching.

The effect on children's attitudes can be damaging, since paying benefits for behavioral problems penalizes getting better. Once a child gets on SSI, he never gets off, warns Ann Marie Sullivan, of the Fordham-Tremont Community Health Center in the Bronx.

Above all, teachers and psychologists question the wisdom of giving cash benefits to the parents of emotionally disturbed children. Often, parental neglect and abuse have created the problem to begin with.

"These children are terribly damaged, but money will not make them better able to cope," says Chuck Merrill, the schol psychologist at New York's Public School 161. "By definition, the parent is unable to take care of the child; how will he or she have the capacity or judgement to spend the money apropriately to address the needs of the child?"

The effort in Congress to rethink children's SSI is long overdue. The rationale for the progrm has neever been clear. Disability payments are intended to replace lost earnings, but children don't work. Some SSI supporters argue that it helps parents purchase medical supplies and services, but Medicaid pays most medical bills of poor parents. Two-thirds of children receiving benefits have no additional expenses anyway. Other advocates have started claiming that SSI replaces the earnings of parents who stay at home to care for their children, but a large number of the parents don't work. The program as established, however, doesn't guarantee either behavior: The $458 monthly check comes with no strings attached.

A House bill aimed at reform would grant cash payments to future beneficiaries only if their disability is so severe as to require institutionalization or who, if they don't have home care, would require institutionalization. All others with medically severe disabilities would qualify for medical care available through a state block grant. A less sweeping reform is moving through theSenate. It continues cash benefits to all children with a severe disability but would also eliminate the age-appropriate standard of disability.

The House block grant approach has a dual advantage of strongly linking children's SSI to the provision of medical care and of eliminating states incentives to sign up as many children as possible. But either bill would be an improvement over the status quo.

It will be a misfortune if the inevitable rhetoric about punishing poor children obscures the facts. Left to its current growth rate, children's SSI will cost $9.2 billion by the year 200-jeopardizing a system that does more harm than good.

Heather Mac Donald is a contributing editor at the Manhattan Institute's City Journal and a fellow of the Institute.

(page 5)

MEMORANDUM TO SENATOR DOLE

DA: May 24, 1995

FR: Alec Vachon

RE: SENATOR CHAFEE'S PROBLEM SEEMS SOLVED

I spoke with Senator Chafee's staffer on Children's SSI late this afternoon. She indicated that her boss would not vote for a more liberal eligibility rules in mark up tomorrow (i.e., possible Conrad amendment), and asked if Senator Chafee could have report language that addressed the concerns of his constituents.

I checked with Committee staff. They would not make promises until they saw specific language, but said would certainly work with Chafee when the report is written. That seems good enough for now. -

(page 1)

MEMORANDUM TO SENATOR DOLE

DA: June 18, 1995

FR: Alec Vachon

RE: YOUR LETTER TO THE WASHINGTON POST

Your letter to the editor re children's SSI was published on Saturday. The letter was printed as sent, except the Post rewrote the second line of the second paragraph--to delete an implicit criticism of the Post (underlined text deleted):

"Enrollment has tripled--not doubled as your editorial states--since 1990, and annual costs have jumped from $1.5 billion to $5 billion."

(doubly underlined) The Post seems iust a bit thin skinned.

(handwritten) Dan; Sheila; (unreadable two names)

(page 2)

WASHINGTON POST, JUNE 16, 1995, (SATURDAY), PAGE A16.

Preserving the Purpose of Children's SSI

A June 7 editorial ("Replacing a Kill With a Cure") called on me to forge a compromise on children's Supplemental Security Income (SSI). As The Post notes, I voted against an amendment on this matter offered by Sen. Kent Conrad during the Finance Subcommittee's markup on welfare reform. That's because I thought Chairman Bob Packwood did a better job in his bill.

Some facts. Enrollment has trippled since 1990, and annual costs have jumped from $1.5 billion to $5 billion. Three factors are responsible. First, Congress instructed the Social Security Administration to find children who belonged in the program. That's fine.

Second, in 1984, in a bill I helped craft, Congress directed Social Security to improve evaluations of children with mental disabilities. It took six years, with considerable prompting from members of Congress, including myself. That caused big growth, but again it was on Congress's orders.

But Social Security went further in 1991, adding new rules that admitted children with modest conditions into a program for children with severe disabilities. Congress did not authorize these rules, and the Finance Committee voted to repeal them.

I did not support Sen. Conrad's amendment because, in my view, it's the wrong policy and could kill the entire program. There are two reasons for this. It would put into statue the lax eligibility regulations, and it would officially convert this program from one for disabled children to a general welfare program.

In 1972, Congress created SSI to provide a cash income to poor elderly and disabled adults unable to work. Needy children were included to help their families with extra expenses resulting from the children's disabilities. But the best data we have indicate that up to two-thirds of families do hot have any extra expenses, and that the money is spent for general household purposes. That is why we have Aid to Families with Dependent Children- although the SSI check is a lot bigger.

There is also the issue of fairness. There is a small number of families-about 5 percent-with huge expenses. No extra expenses or huge expenses, all children get the same check.

The Finance Committee has not tackled these problems yet, but it should and I believe it will.

The Finance Committee bill tightens eligibility, but not as much more than the Conrad proposal. And the Finance Committee bill treats children affected by the new rules more generously. All children would have their situations reviewed again to see if they requalify, and, in any case, no child would leave the program before Jan. 1, 1997. The Conrad proposal could drop some children almost immediately.

As the editorial notes, I have been a long-standing advocate for people with disabilities. I am proud of my record. But not every program for the disabled is perfect, and this is one such case.

BOB DOLE

U.S. Senator (R-Kan.)

Washington

(page 3)

MEMORANDUM TO SENATOR DOLE

DA: March 16, 1995

FR: Alec Vachon

RE: SENATE FINANCE SUBCOMMITTEE HEARING ON "SOARING COSTS OF SOCIAL SECURITY'S TWO DISABILITY PROGRAMS"

* The Subcommittee on Social Security & Family Policy will meet on Wednesday, March 22, 1995, at 10:00 a.m. in Dirksen 215, to examine the sharp growth in the SSI and SSDI over the past 5 years. For example, between 1989 and 1994, SSI rolls jumped 42%, from 4.1 to 5.8 million recipients, and expenditures from $15 to $24 billion. CBO projects SSI rolls will increase by 2.2 million persons by 2000, and expenditures will rise to $42.5 billion. BTW, this will be the first Finance hearing on any aspect of SSI since 1986.

* [N.B. Subcommittee hearing is preparation for full Committee hearing during week of March 27th on SSI reform proposals--which will focus on cuts in eligibility for children, aliens, and drug addicts/alcoholics.]

* WITNESSES ON MARCH 22ND:

--Senator William S. Cohen;

--Social Security Commissioner Shirley S. Chater;

--David Koitz of the Congressional Research Service; and

--The Honorable Jim Slattery, Chairman, Childhood Disability Commission.

Yvonne indicates your schedule is open at that time

DO YOU WISH TO ATTEND THE SUBCOMMITTEE HEARING?

YES (blank) NO (handwritten check mark)

IF YES, DO YOU WANT ME TO PREPARE AN OPENING STATEMENT FOR YOU?

YES (handwritten check mark) NO (blank)

cc: S. Burke

(handwritten) Dan; Sheila

(page 4)

(handwritten) Alev V- (unreadable)

THE WASHINGTON POST, JUNE 18, 1995 (SUNDAY), P. C7.

Teaching Johnny to Fail

The Mixed-Up Messages ofDisability Welfare for Troubled Kids

By Heather Mac Donald

ANOTHER CHILDREN's welfare debate is about to hit Congress-reform of the federal benefits program for disabled poor children, known as Supplemental Security Income.

Congress could not have chosen a more emotionally charged issue. Welfare advocates are already preparing images of children dumped in the streets if the proposed House and Senate bills become law.

Yet the people who work most closely with poor children-teachers, pediatricians and social workers-argue that SSI puts marginally disabled or non-disabled children on the dole life and often hides the children's real problem: abusive or neglectful parents. These front-line observers should be heard.

Children's SSI has expanded enormously in the last five years, driven by three powerful economic incentives: Parents receive roughly three times more money from SSI than from Aid to Families with Dependant Children; states save money by shifting their AFDC caseload to SSI since the latter is funded by the federal government, with optional state supplementation; and mothers with disabled children are exempt from welfare work requirements.

Until 1990, however, the Social Security Administration kept the demand for SSI in check by restricting benefits to children with a medically defined severe impairment, such as cerebral palsy or cystic fibrosis. But in 1990, the Supreme Court ordered the agency to include children whose disabilities were not severe if they were unable to function in an "age-appropriate" manner.

The result was dramatic. The number of children receiving SSI shot up threefold: 900,000 children will collect $5 billion this year. Another 200,000 children will join the rolls by the end of 1995.

The Supreme Court also radically altered the composition of the rolls, by opening them to the vast and growing world of learning and behavioral disorders. Children who fall behind in school or who act violently in class may now be classified as functionally disabled.

Two-thirds of the new beneficiaries since 1990 claim "mental impairment."

Although many teachers and social workers support disability payments for the severely disabled, it is hard to find proponents for the program as now structured.

"Teachers are disgusted with it," says Jeff Nussbaum, a special education music teacher at Park West High School in Manhattan. "A kid gets classified as 'emotionally disturbed.' What that means is anyone's guess. He can be violent, really rotten, and he gets the dole."

In effect, critics argue, SSI has created a perverse incentive system for parents: "Parents whose children ahve minimal handicaps try to get their children into special education classes so their kids can qualify for SSI," complains a school psychologist at New York's Central Park East Secondary School. A student at a New York City elementary school recently told a story in a symbolic play class that illustrates the impact of SSI on the nation's poorest communities. Acting out her tale with dolls, she describes a mother of four who had adopted two more children. Although the new siblings weren't working out, the mother planned to keep them anyway, the girl explained, because she wanted the extra $100 in SSI payments they were bringing in.

"This was a special education student," says Beth Mahaney, a school psychology aide. "She doesn't understand much, but she already understands how the system works."

Some teachers believe that the prospect of SSI payments leads parents to coach their children to fail classes or misbehave in school. Eighty-one percent of instructors and special education counselors polled in Arkansas said they believe their students on SSI had been told by their parents to act up in class, and 79 percent taught that once a child qualifies for SSI, his motivation to succeed decreases. The Social Security Administration, however, has been unable to document such parental coaching.

The effect on children's attitudes can be damaging, since paying benefits for behavioral problems penalizes getting better. Once a child gets on SSI, he never gets off, warns Ann Marie Sullivan, of the Fordham-Tremont Community Health Center in the Bronx.

Above all, teachers and psychologists question the wisdom of giving cash benefits to the parents of emotionally disturbed children. Often, parental neglect and abuse have created the problem to begin with.

"These children are terribly damaged, but money will not make them better able to cope," says Chuck Merrill, the schol psychologist at New York's Public School 161. "By definition, the parent is unable to take care of the child; how will he or she have the capacity or judgement to spend the money apropriately to address the needs of the child?"

The effort in Congress to rethink children's SSI is long overdue. The rationale for the progrm has neever been clear. Disability payments are intended to replace lost earnings, but children don't work. Some SSI supporters argue that it helps parents purchase medical supplies and services, but Medicaid pays most medical bills of poor parents. Two-thirds of children receiving benefits have no additional expenses anyway. Other advocates have started claiming that SSI replaces the earnings of parents who stay at home to care for their children, but a large number of the parents don't work. The program as established, however, doesn't guarantee either behavior: The $458 monthly check comes with no strings attached.

A House bill aimed at reform would grant cash payments to future beneficiaries only if their disability is so severe as to require institutionalization or who, if they don't have home care, would require institutionalization. All others with medically severe disabilities would qualify for medical care available through a state block grant. A less sweeping reform is moving through theSenate. It continues cash benefits to all children with a severe disability but would also eliminate the age-appropriate standard of disability.

The House block grant approach has a dual advantage of strongly linking children's SSI to the provision of medical care and of eliminating states incentives to sign up as many children as possible. But either bill would be an improvement over the status quo.

It will be a misfortune if the inevitable rhetoric about punishing poor children obscures the facts. Left to its current growth rate, children's SSI will cost $9.2 billion by the year 200-jeopardizing a system that does more harm than good.

Heather Mac Donald is a contributing editor at the Manhattan Institute's City Journal and a fellow of the Institute.

(page 5)

MEMORANDUM TO SENATOR DOLE

DA: May 24, 1995

FR: Alec Vachon

RE: SENATOR CHAFEE'S PROBLEM SEEMS SOLVED

I spoke with Senator Chafee's staffer on Children's SSI late this afternoon. She indicated that her boss would not vote for a more liberal eligibility rules in mark up tomorrow (i.e., possible Conrad amendment), and asked if Senator Chafee could have report language that addressed the concerns of his constituents.

I checked with Committee staff. They would not make promises until they saw specific language, but said would certainly work with Chafee when the report is written. That seems good enough for now. -

(page 1)

MEMORANDUM TO SENATOR DOLE

DA: June 18, 1995

FR: Alec Vachon

RE: YOUR LETTER TO THE WASHINGTON POST

Your letter to the editor re children's SSI was published on Saturday. The letter was printed as sent, except the Post rewrote the second line of the second paragraph--to delete an implicit criticism of the Post (underlined text deleted):

"Enrollment has tripled--not doubled as your editorial states--since 1990, and annual costs have jumped from $1.5 billion to $5 billion."

(doubly underlined) The Post seems iust a bit thin skinned.

(handwritten) Dan; Sheila; (unreadable two names)

(page 2)

WASHINGTON POST, JUNE 16, 1995, (SATURDAY), PAGE A16.

Preserving the Purpose of Children's SSI

A June 7 editorial ("Replacing a Kill With a Cure") called on me to forge a compromise on children's Supplemental Security Income (SSI). As The Post notes, I voted against an amendment on this matter offered by Sen. Kent Conrad during the Finance Subcommittee's markup on welfare reform. That's because I thought Chairman Bob Packwood did a better job in his bill.

Some facts. Enrollment has trippled since 1990, and annual costs have jumped from $1.5 billion to $5 billion. Three factors are responsible. First, Congress instructed the Social Security Administration to find children who belonged in the program. That's fine.

Second, in 1984, in a bill I helped craft, Congress directed Social Security to improve evaluations of children with mental disabilities. It took six years, with considerable prompting from members of Congress, including myself. That caused big growth, but again it was on Congress's orders.

But Social Security went further in 1991, adding new rules that admitted children with modest conditions into a program for children with severe disabilities. Congress did not authorize these rules, and the Finance Committee voted to repeal them.

I did not support Sen. Conrad's amendment because, in my view, it's the wrong policy and could kill the entire program. There are two reasons for this. It would put into statue the lax eligibility regulations, and it would officially convert this program from one for disabled children to a general welfare program.

In 1972, Congress created SSI to provide a cash income to poor elderly and disabled adults unable to work. Needy children were included to help their families with extra expenses resulting from the children's disabilities. But the best data we have indicate that up to two-thirds of families do hot have any extra expenses, and that the money is spent for general household purposes. That is why we have Aid to Families with Dependent Children- although the SSI check is a lot bigger.

There is also the issue of fairness. There is a small number of families-about 5 percent-with huge expenses. No extra expenses or huge expenses, all children get the same check.

The Finance Committee has not tackled these problems yet, but it should and I believe it will.

The Finance Committee bill tightens eligibility, but not as much more than the Conrad proposal. And the Finance Committee bill treats children affected by the new rules more generously. All children would have their situations reviewed again to see if they requalify, and, in any case, no child would leave the program before Jan. 1, 1997. The Conrad proposal could drop some children almost immediately.

As the editorial notes, I have been a long-standing advocate for people with disabilities. I am proud of my record. But not every program for the disabled is perfect, and this is one such case.

BOB DOLE

U.S. Senator (R-Kan.)

Washington

(page 3)

MEMORANDUM TO SENATOR DOLE

DA: March 16, 1995

FR: Alec Vachon

RE: SENATE FINANCE SUBCOMMITTEE HEARING ON "SOARING COSTS OF SOCIAL SECURITY'S TWO DISABILITY PROGRAMS"

* The Subcommittee on Social Security & Family Policy will meet on Wednesday, March 22, 1995, at 10:00 a.m. in Dirksen 215, to examine the sharp growth in the SSI and SSDI over the past 5 years. For example, between 1989 and 1994, SSI rolls jumped 42%, from 4.1 to 5.8 million recipients, and expenditures from $15 to $24 billion. CBO projects SSI rolls will increase by 2.2 million persons by 2000, and expenditures will rise to $42.5 billion. BTW, this will be the first Finance hearing on any aspect of SSI since 1986.

* [N.B. Subcommittee hearing is preparation for full Committee hearing during week of March 27th on SSI reform proposals--which will focus on cuts in eligibility for children, aliens, and drug addicts/alcoholics.]

* WITNESSES ON MARCH 22ND:

--Senator William S. Cohen;

--Social Security Commissioner Shirley S. Chater;

--David Koitz of the Congressional Research Service; and

--The Honorable Jim Slattery, Chairman, Childhood Disability Commission.

Yvonne indicates your schedule is open at that time

DO YOU WISH TO ATTEND THE SUBCOMMITTEE HEARING?

YES (blank) NO (handwritten check mark)

IF YES, DO YOU WANT ME TO PREPARE AN OPENING STATEMENT FOR YOU?

YES (handwritten check mark) NO (blank)

cc: S. Burke

(handwritten) Dan; Sheila

(page 4)

(handwritten) Alev V- (unreadable)

THE WASHINGTON POST, JUNE 18, 1995 (SUNDAY), P. C7.

Teaching Johnny to Fail

The Mixed-Up Messages ofDisability Welfare for Troubled Kids

By Heather Mac Donald

ANOTHER CHILDREN's welfare debate is about to hit Congress-reform of the federal benefits program for disabled poor children, known as Supplemental Security Income.

Congress could not have chosen a more emotionally charged issue. Welfare advocates are already preparing images of children dumped in the streets if the proposed House and Senate bills become law.

Yet the people who work most closely with poor children-teachers, pediatricians and social workers-argue that SSI puts marginally disabled or non-disabled children on the dole life and often hides the children's real problem: abusive or neglectful parents. These front-line observers should be heard.

Children's SSI has expanded enormously in the last five years, driven by three powerful economic incentives: Parents receive roughly three times more money from SSI than from Aid to Families with Dependant Children; states save money by shifting their AFDC caseload to SSI since the latter is funded by the federal government, with optional state supplementation; and mothers with disabled children are exempt from welfare work requirements.

Until 1990, however, the Social Security Administration kept the demand for SSI in check by restricting benefits to children with a medically defined severe impairment, such as cerebral palsy or cystic fibrosis. But in 1990, the Supreme Court ordered the agency to include children whose disabilities were not severe if they were unable to function in an "age-appropriate" manner.

The result was dramatic. The number of children receiving SSI shot up threefold: 900,000 children will collect $5 billion this year. Another 200,000 children will join the rolls by the end of 1995.

The Supreme Court also radically altered the composition of the rolls, by opening them to the vast and growing world of learning and behavioral disorders. Children who fall behind in school or who act violently in class may now be classified as functionally disabled.

Two-thirds of the new beneficiaries since 1990 claim "mental impairment."

Although many teachers and social workers support disability payments for the severely disabled, it is hard to find proponents for the program as now structured.

"Teachers are disgusted with it," says Jeff Nussbaum, a special education music teacher at Park West High School in Manhattan. "A kid gets classified as 'emotionally disturbed.' What that means is anyone's guess. He can be violent, really rotten, and he gets the dole."

In effect, critics argue, SSI has created a perverse incentive system for parents: "Parents whose children ahve minimal handicaps try to get their children into special education classes so their kids can qualify for SSI," complains a school psychologist at New York's Central Park East Secondary School. A student at a New York City elementary school recently told a story in a symbolic play class that illustrates the impact of SSI on the nation's poorest communities. Acting out her tale with dolls, she describes a mother of four who had adopted two more children. Although the new siblings weren't working out, the mother planned to keep them anyway, the girl explained, because she wanted the extra $100 in SSI payments they were bringing in.

"This was a special education student," says Beth Mahaney, a school psychology aide. "She doesn't understand much, but she already understands how the system works."

Some teachers believe that the prospect of SSI payments leads parents to coach their children to fail classes or misbehave in school. Eighty-one percent of instructors and special education counselors polled in Arkansas said they believe their students on SSI had been told by their parents to act up in class, and 79 percent taught that once a child qualifies for SSI, his motivation to succeed decreases. The Social Security Administration, however, has been unable to document such parental coaching.

The effect on children's attitudes can be damaging, since paying benefits for behavioral problems penalizes getting better. Once a child gets on SSI, he never gets off, warns Ann Marie Sullivan, of the Fordham-Tremont Community Health Center in the Bronx.

Above all, teachers and psychologists question the wisdom of giving cash benefits to the parents of emotionally disturbed children. Often, parental neglect and abuse have created the problem to begin with.

"These children are terribly damaged, but money will not make them better able to cope," says Chuck Merrill, the schol psychologist at New York's Public School 161. "By definition, the parent is unable to take care of the child; how will he or she have the capacity or judgement to spend the money apropriately to address the needs of the child?"

The effort in Congress to rethink children's SSI is long overdue. The rationale for the progrm has neever been clear. Disability payments are intended to replace lost earnings, but children don't work. Some SSI supporters argue that it helps parents purchase medical supplies and services, but Medicaid pays most medical bills of poor parents. Two-thirds of children receiving benefits have no additional expenses anyway. Other advocates have started claiming that SSI replaces the earnings of parents who stay at home to care for their children, but a large number of the parents don't work. The program as established, however, doesn't guarantee either behavior: The $458 monthly check comes with no strings attached.

A House bill aimed at reform would grant cash payments to future beneficiaries only if their disability is so severe as to require institutionalization or who, if they don't have home care, would require institutionalization. All others with medically severe disabilities would qualify for medical care available through a state block grant. A less sweeping reform is moving through theSenate. It continues cash benefits to all children with a severe disability but would also eliminate the age-appropriate standard of disability.

The House block grant approach has a dual advantage of strongly linking children's SSI to the provision of medical care and of eliminating states incentives to sign up as many children as possible. But either bill would be an improvement over the status quo.

It will be a misfortune if the inevitable rhetoric about punishing poor children obscures the facts. Left to its current growth rate, children's SSI will cost $9.2 billion by the year 200-jeopardizing a system that does more harm than good.

Heather Mac Donald is a contributing editor at the Manhattan Institute's City Journal and a fellow of the Institute.

(page 5)

MEMORANDUM TO SENATOR DOLE

DA: May 24, 1995

FR: Alec Vachon

RE: SENATOR CHAFEE'S PROBLEM SEEMS SOLVED

I spoke with Senator Chafee's staffer on Children's SSI late this afternoon. She indicated that her boss would not vote for a more liberal eligibility rules in mark up tomorrow (i.e., possible Conrad amendment), and asked if Senator Chafee could have report language that addressed the concerns of his constituents.

I checked with Committee staff. They would not make promises until they saw specific language, but said would certainly work with Chafee when the report is written. That seems good enough for now.

Export

Position: 219 (14 views)